“I don’t cough, I cry”

- Dec 3, 1984

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 9, 2021

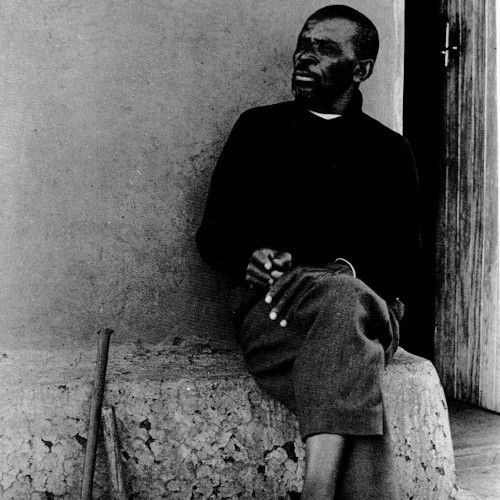

Nkalegeng Kaizer Mamailana lives in the village of Mmafefe – beneath the old Darlton Asbestos mine.

He was a young man when he worked at the mine. But today he looks old and worn out.

“I cannot breathe and I cannot walk very far,” he says with sadness in his eyes. “But I am lucky.

Most of my old friends are dead. They worked in the asbestos mines for a long time. I also worked in the asbestos mine. But I was also in the gold mines for many years. Maybe that’s why I’m not dead yet. If it wasn’t for the asbestos mines, then my friends would still be alive.”

Mr Maimalana told Learn and Teach about the lives of the men and women who worked in the old asbestos mines. These are his words.

A SPECIAL DAY

“My first job was in the gold mines of Johannesburg. Iworked there for five years. Then I came home.

I was in love. Her name was Sekgopetjane Lesufi. She also came from Mmafefe village. Our wedding was a special day. The women brewed beer and cooked meat. An ox was slaughtered. All my neighbours came to the feast.

You know sometimes in those days men got married by letter. It was a custom. While a man was away at the mines, his parents found him a wife. They wrote him a letter saying: ‘Come home. You have a wife.’ I was lucky. I chose my own wife.

CARS WITH WHEELS LIKE BICYCLES

At the time of my wedding white men came to our village. They came in old cars with thin wheels like a bicycle. And they wore shiny boots and heImets.

The white men were not the owners of the mines. The big firms often allowed smaller firms to mine on their land.

I wanted to stay with my new wife. So I took a job on one of these small mines. I was happy to get work near the village.

WORKING FOR “STOCK”

Everyday we climbed the mountain. We had to go up 500 feet before we began work. We dug tunnels into the mountain with picks and shovels.

We carried our food and tools with us. We also carried our own water. There was no water up there in the mountains.

Inside the tunnel we made holes in the rock. We used iron bars and a hammer. Only later did the white men bring machines called ‘umadumelana’ (an air drill).

Then the makgua put dynamite in the holes. The dynamite blew the rocks out of the mountain. We then filled big sacks with the rocks.

You know, those makgua robbed us. They didn’t pay us wages. We just worked for ‘stock’. This means they paid us for each bag of asbestos we filled. In 1959 they paid us 17 shillings a bag – and sometimes it took four days to fill one bag.

Sometimes we worked for a whole day making the holes for the dynamite. Then after the explosion we found no asbestos in the rock. But on other days we were lucky. We filled many bags in one day.

Some men took their wives into the mountains. The wives helped them to fill the bags more quickly.

The money wasn’t even enough to buy mealie meal. But I didn’t take Sekgopetjane with me. She grew crops near the village to feed our family.

ROCKS ON OUR SHOULDERS

Sometimes I spent many days and nights in the mountains. We started work at four o’clock in the morning. We worked until after the sun went down.

We used donkeys to carry the bags down the mountain. But sometimes the donkeys slipped. Many fell down the mountain and died. Then we had to carry the bags of rock on our shoulders.

Most of the women and children worked at the mill. They did ‘cobbing’. This means they broke the asbestos off the rock -with big hammers. They also worked for ‘stock’. But the mines paid them less than the men.

BROKEN BONES AND NO COMPENSATION .

Sometimes the makgua took our bags away. They said they were going to count the rocks. Then they were gone. Amen! We never saw them again. They robbed us. That’s how I got this hammer and bar.

One white man stole my bags of rock. But he left his tools behind. So I kept them.

The mines were dangerous. Many men broke their bones up in the mountains. Some of them were even paralysed.

The mines paid no compensation in those days. And they didn’t tell us about the diseases. Many men only found they had a disease from asbestos when they went to the gold mines. The gold mines always X-rayed new workers.

I went to work on the gold mines again. I needed more money. And I was afraid of the mines in the mountains.

My last job was at a mine in Phalaborwa. I left this mine a few years ago. Now I live on their pension. They give me R80 every two months.”

MEMORIES AND TEARS

Today Mr Mamailana and his wife try to keep alive in Mmafefe. The pension isn’t enough to feed them. They have no goats and no cattle. So they grow vegetables near the old fig tree down by the river.

But Mr Mamailana cannot work for long. He loses his breath quickly. He often sits down under the tree to rest.

At these times he remembers his friends who were killed by the mines. And he knows that he has the same disease as them.

“But I don’t cough,” he says. “I cry.”

Comments