“Hands off Turfloop”

- Jul 3, 1989

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 17, 2021

There are not many universities in the world like Turfloop. While students in many universities study in peace and freedom, the students at Turfloop study under the barrel of the gun.

Here, the South African Defence Force (SADF), together with the South African Police (SAP) and the Lebowa Police, help the university authorities to keep “law and order” on the university campus the only way they know how — with tanks and guns.

And when the students protest against the presence of their unwanted “guests”, they have been sjambokked, teargassed, detained, expelled and sometimes even shot.

Learn and Teach drove to Turfloop University — also called the University of the North. It stands thirty kilometres east of Pietersburg, in Mankweng in the Northern Transvaal.

As we drove in, we passed army trucks and soldiers patrolling the campus. It felt like an army camp. We were relieved to arrive at the hostels where the students greeted us warmly and began to tell us about the university’s history of resistance to apartheid and the many years of army and police harassment.

“BUSH” UNIVERSITIES

Turfloop University was started one year after the government made a new apartheid law called the ‘Extension of University Education Act of 1959’. When this law was passed, black students could no longer go to the “open” universities — like the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town.

So, universities for blacks were started around the country. They were built far from the big cities, in the bush — and they soon became known as “bush” universities.

Turfloop became the university for Sotho, Tsonga and Venda speaking students. The University of Zululand in Ulundi for Zulus, and Fort Hare, which had been opened in 1915 in Alice in the Ciskei for Xhosas. “Coloureds” went to the University of the Western Cape in Bellville and Indians to Durban-Westville, near Durban.

THE SEATS OF APARTHEID

From the beginning black students were angry at being forced to study at the “bush” universities. But it was not until 1969 that students from these universities came together to fight apartheid education.

They met at Turfloop to form the South African Student Organisation (SASO). This organisation fought for Student Representative Councils (SRC’s) and other basic rights at these universities. Steve Biko was elected the first SASO president.

Three years later, the president of the Turfloop SRC, Abraham Tiro, stood up to give a speech at the graduation ceremony. University teachers, parents and government officials were invited. It was a hot day. The government officials and university authorities, mostly whites, were given seats in the shade, while the parents and students had to sit under the blazing sun, at the very back.

When Tiro spoke, he attacked this clear example of apartheid and he also spoke out against Bantu Education.

The speech angered the university and soon afterwards, Tiro and other SRC members were expelled. The students started a boycott of classes in solidarity with the expelled students. The authorities’ reply was to close the university and send the students home.

After being expelled, Tiro went into exile in Botswana where he was killed by a letter bomb in 1974. Three years later, Steve Biko was tortured to death by the SAP, and SASO was banned together with 17 other organisations.

RECIPE FOR FAILURE

Since then, Turfloop has seen many students expelled and many boycotts. In 1985, students boycotted classes in protest against the unfair university rules.

“The university authorities were making rules which were sure recipes for failure for the students,” says a student. “For example, it said that if students did not complete their degree in a certain number of years, they would not be allowed to continue studying.

“We students called this ‘academic terrorism’ and we challenged the university to change these rules.” Finally, the university authorities dropped the rule.

“We were also protesting against some of the teachers at the university. These teachers came from Afrikaans universities like the Rand Afrikaans University (RAU) and were racists.

“One of the teachers said that no black student could pass Maths the first time. He said blacks are too stupid to be able to learn Maths. And he said that black women are even more stupid — they could not pass Maths in third year without repeating it. One of the teachers was forced to resign because of our protests.”

ROOM-TO-ROOM RAIDS

“These protests were a very important time for us,” said another student. “They taught us the power of unity. At the time we were waging our struggles under the banner of the Azanian Students Organisation (AZASO) which was formed in 1979.

“AZASO members were targets for the Pietersburg Security Police. In May 1985, the South African and Lebowa police came onto the campus and started a room-to-room raid. Fifteen students were detained. More than 50 were injured and had to go to hospital.

“A few weeks later, two members of the Turf Women’s Group were detained and tortured. Josephine Moshobane died of brain damage two weeks after she was released. The SRC organised a protest meeting against the police. The police dispersed us and shot three students and stabbed two others.

“When, in 1986, AZASO changed its name to the South African National Students’ Congress (SANSCO), police harassment continued.

THE ARMY CREEPS IN

On 11 June 1986, on the same day as the second state of emergency was declared, soldiers invaded the campus.

A law student told us: “We were attending classes normally and everyone was preparing for the June examinations. Suddenly, at midnight, we heard shouting that soldiers were on campus. When we went outside, we found that they were everywhere.”

The next morning 22 students, including seven SRC members, were detained. A Philosophy teacher, Mr Louis Mnguni, was also detained. Later that year, the university librarian, Joyce Mabhudafasi, was also taken. The police and the army closed the university after ordering students to leave the campus.

One of the students who was in detention says: “The university did not allow us to study for the two years we were in jail. They said that Turfloop will never be open to ‘revolutionaries’.”

“After our comrades were detained, the students went on a boycott demanding the withdrawal of the troops,” says a third-year education student. “We also called for the setting up of the SRC that the university had banned. We demanded the release of our fellow students, the lifting of the state of emergency and the right to hold meetings freely on campus. The university fought back by dismissing more than 500 students.”

PINK CARDS

The army troops have remained on campus ever since. Every now and then, they send out pamphlets to students, saying: “The security forces are here to protect life and property. To uproot revolutionaries and protect law- abiding citizens.”

In 1986, the army stopped students from getting visitors on campus. Each student had to carry a pink card with their name and the logos of the SADF, SAP and the Lebowa Police on it. These cards were signed by a Colonel Lombard.

The army’s presence has not dampened the spirit of the students. This year in March, the students again raised their voices in protest against the troops on campus.

Two weeks later, the university still had not met the demands of the students. A boycott followed. The “campus security guards”, who the students call the “Black Jacks”, opened fire on students. Three students were shot. One of them, Klaas Puane, lost his sight in one eye.

THE CAMPAIGN TAKES OFF

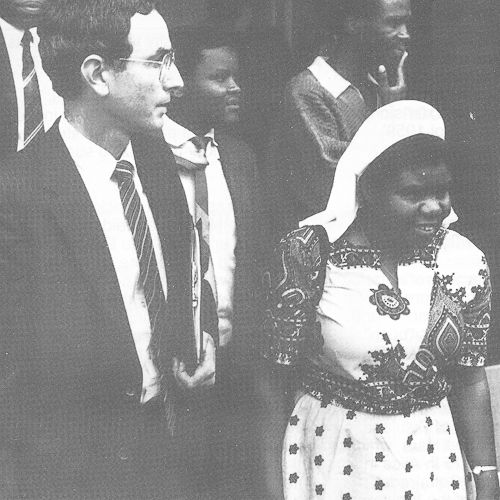

It was then that the Turfloop SRC turned to their comrades at other universities for support. Lindsay Falkov, who is the president of National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), told us: “When NUSAS heard about the problems of our fellow students at Turfloop, we knew that we could not just sit back.

“So we held mass meetings to tell students and lecturers about what was happening at Turfloop. We asked people to sign solidarity cards. More than 13 000 people signed them. On 26 April, we held a big, succesful rally.”

Support did not only come from students and teachers. The South African Council of Churches (SACC), the Call of Islam, the Atteridgeville- Saulsville Residents’ Organisation, Equal Opportunity Foundation and the Lawyers for Human Rights all joined together with the students to form the “Hands Off Turfloop!” campaign.

Members of the “Hands Off Turf loop!” campaign met Turfloop’s vice-principal, John Malatji. “We demanded the withdrawal of the army from campus,” says Saki Macozoma of the SACC. “

The university said they were waiting for the troops to finish building their camp in Mankweng before they could move out. We said it was not the university’s business to worry about where the army goes. The army stayed somewhere before coming to the university, so they should go back to that place!”

Matters did not end there. A week later, men believed to be Security Branch officers raided the room of the SRC president, Ernest Khoza, and assaulted him.

“Myself and other members of the SRC have been living in fear for our lives ever since,” says Khoza. “But we will not rest until the day that our universities become homes of learning — and not homes for the army. And until we see apartheid thrown into the dustbin of history — where it belongs. On that day, the doors of learning and culture shall be open to all!”

Comments